By Dan Gephart, April 11, 2023

By Dan Gephart, April 11, 2023

Long-time members of FELTG Nation recall Meghan Droste as an engaging instructor and writer, who could break down difficult subjects into easy-to-understand guidance. At the same time, she’d often leave this FELTG Newsletter Editor with an earworm or two.

Ms. Droste, now an administrative judge with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, will kick off Day 1 of FELTG’s upcoming Emerging Issues in Federal Employment Law event, presenting Avoiding Pitfalls: Advice from an EEOC AJ on Tuesday, April 18, 2023, at 10:30 am ET.

[The theme for Day 1 is Lessons Learned and we’ll also have presentations from former MSPB Member Tristan Leavitt and FELTG’s own Joseph Schimansky. Check out the full agenda. Register for one session, one day, the whole event or any combination of sessions – it’s up to you.]

We recently caught up with Ms. Droste to discuss her career transition and what she plans to cover in her session on April 18.

DG: As a practicing attorney, you were very familiar with the EEO process. Did anything surprise you or was there anything about the process you didn’t realize until after you became an administrative judge?

MD: When I first started it was very interesting to see all of the work that is done “behind the scenes” — everything that AJs have to juggle that the parties don’t see. But I think the most surprising thing was the number of self-represented, or pro se, complainants who we see in the Washington Field Office. As a complainant’s representative I of course did not have any involvement in those types of cases, and even when I represented a Federal agency, I often encountered representatives on the other side. The process is meant to be accessible for self-represented complainants and it has been very interesting to see just how many there are.

DG: What is the most common misunderstanding about the EEO process?

MD: I think one of the most common misunderstandings, from both complainants and agencies, is an assumption that the hearings process is informal and not as serious as litigation in Federal court. AJs don’t wear robes or sit in courtrooms, but we still issue orders and set schedules that the parties have to abide by. It seems that some parties don’t understand that and think that deadlines are optional or that they can ignore their obligations that we set out in our orders or are in the EEOC’s Management Directive 110.

DG: What’s your advice to parties who are new to the EEO process on the importance of the initial conference?

MD: It is so important for the parties to be prepared for an initial conference (IC). By the time I hold an IC, I have reviewed the Report of Investigation, the parties’ Preliminary Case Information submissions, and anything else that they have uploaded to the Public Portal/FedSep; I expect the parties to have done the same and to be familiar with their case. The parties should be ready to address all of the topics outlined in the Acknowledgment Order and answer any questions I have for them about the record or their discovery needs. If they aren’t prepared, it slows down the IC and can result in a party waiving its right to raise an issue or object to something that I cover during the IC.

DG: You will be discussing the importance of civility in the EEO process at Emerging Issues in Federal Employment Law. Can you provide an example where lack of civility negatively impacted a party’s position in settlement or litigation?

MD: One way that this comes to my attention is when parties are filing a motion for an extension or a motion to compel. I generally do not see the parties’ interactions with each other, but when it comes time to file a motion that requires the party to note the opposing parties’ objections to the motion or to refer to the parties’ discussions about discovery, I see copies of correspondence between the parties as exhibits.

It’s easy to see when the parties are being civil to one another and when they are not. It’s also easy to see how, as the parties become more heated, they are less willing to work with each other to resolve routine issues. This impacts the issue they are filing the motion for and can make any later settlement discussions more difficult, if not impossible, as each side digs into their own positions and are unwilling to compromise.

DG: Agencies often miss the mark in their pleadings. What’s the most common problem with pleadings and how do you suggest that problem be fixed?

MD: Two things come to mind right away, and both are easy for agencies to fix. The first is exceeding the page limits for motions or otherwise failing to follow the requirements I set out in the Case Management Order (CMO). I remind the parties during every IC to review the CMO thoroughly because each AJ does things a little differently. Despite this, I can always tell when a party has failed to do so, and it can have a real impact for them. For example, if a party exceeds the page limit, I stop reading the motion at the last allowable page. I don’t give any consideration to any argument that comes after the page limit. The second common problem is allowing the agency’s arguments to creep into the statement of facts. The statement of facts should be, as it sounds, just the facts. An agency loses some credibility with me in the summary judgment process if it tries to spin the facts rather than presenting them without argument.

Have your own questions for Judge Droste? Register now for Emerging Issues in Federal Employment Law. Gephart@FELTG.com

By

By

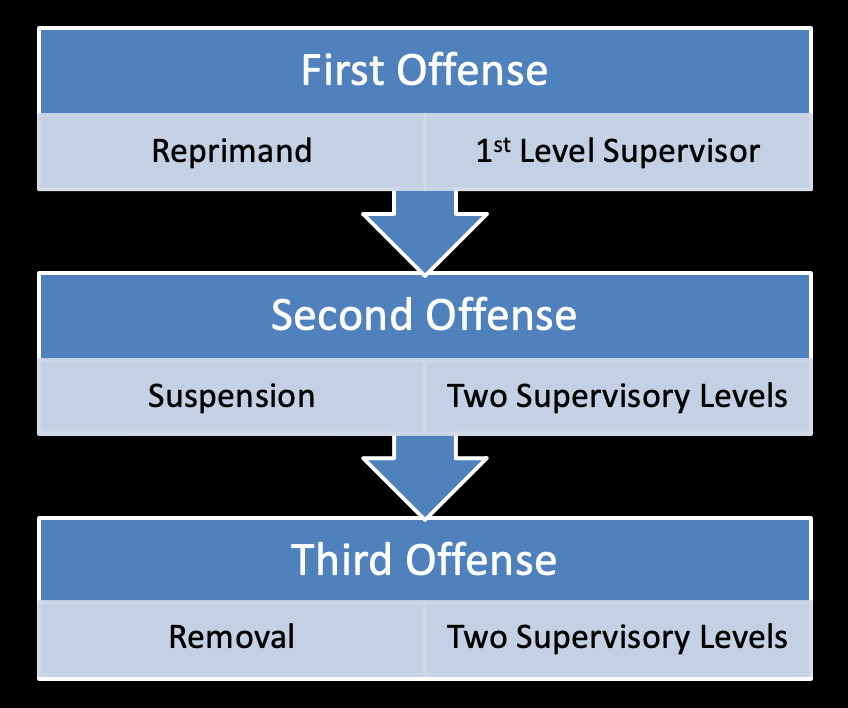

A recent MSPB nonprecedential decision has me scratching my head, as the outcome appears to go against over 40 years of case precedent. I wrote about the facts of the case in a

A recent MSPB nonprecedential decision has me scratching my head, as the outcome appears to go against over 40 years of case precedent. I wrote about the facts of the case in a  There are always two sides to a reasonable accommodation (RA) case: the agency’s side and the complainant’s side. While a lot of our training programs at FELTG focus on avoiding agency liability, there’s another aspect to this that’s important to mention, and that’s doing the right thing for the employee who requests accommodation. We see too many instances where an agency handles an RA request improperly, and it exacerbates the employee’s medical condition, causing further harm.

There are always two sides to a reasonable accommodation (RA) case: the agency’s side and the complainant’s side. While a lot of our training programs at FELTG focus on avoiding agency liability, there’s another aspect to this that’s important to mention, and that’s doing the right thing for the employee who requests accommodation. We see too many instances where an agency handles an RA request improperly, and it exacerbates the employee’s medical condition, causing further harm.